October 23, 2025

Basho Haiku Walkway #06

Basho’s Journey in Three Scenes

With this sixth and final chapter of the Basho Haiku Walkway, we come to the poignant moments when the poet set off on his legendary journey to the north.From the threshold at Senju, where he bid farewell to Edo as spring faded, to his own humble hut in Fukagawa, where he reflected on the passing of time and the inevitability of change, these verses capture Basho’s sensitivity to the transient nature of life and travel.

We hope this final installment allows you to experience, as Basho did, that every departure—whether from a season, a home, or a city—is also the beginning of a new journey.

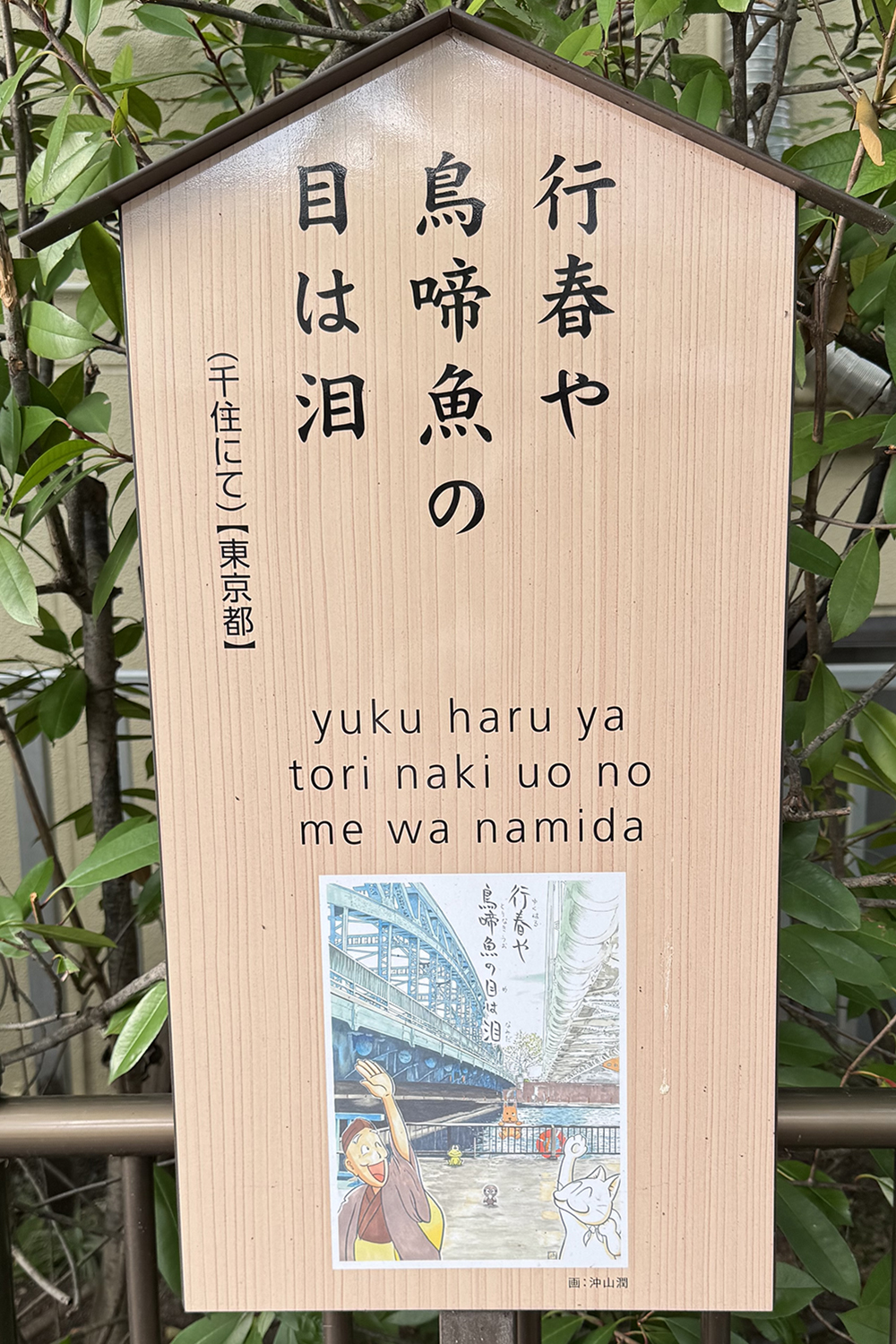

Haiku 16. Senju, Tokyo

行春や 鳥啼魚 目は泪

(Yuku haru ya / Tori naki uo no / Me wa namida)

The spring departs—

birds are singing,

fish seem to weep.

Behind the Haiku - Discover the hidden stories behind each haiku -

1. The setting: Senju, a gateway to EdoBasho wrote this haiku at Senju, one of the major post stations (shukuba) on the road leading north from Edo (modern-day Tokyo). Travelers departing from Edo crossed the Arakawa River at Senju to begin their journey along the Mutsu Road into the northern provinces.

This location symbolized both farewell and new beginnings—an emotional threshold where one leaves behind the familiar capital and steps into the unknown countryside. Basho and his companion Sora began their legendary journey to the north, later chronicled in Oku no Hosomichi (The Narrow Road to the Deep North), at this very spot.

2. The theme of departure and the pathos of spring’s end

The opening phrase “Yuku haru ya” (行春や) means “spring is passing” or “spring departs.” In classical Japanese aesthetics, the end of spring is often associated with mono no aware—the poignant awareness of impermanence and the fleeting nature of life and seasons.

The imagery of birds singing (tori naki) and fish whose eyes appear wet with tears (uo no me wa namida) reflects the poet’s emotions. The fish are not literally weeping; rather, their glistening eyes and the rippling river water evoke an impression of shared sorrow, as if nature itself were mourning the season’s passing.

3. A symbolic beginning of the journey

For Basho, leaving Edo marked more than a geographical departure; it was a spiritual step away from worldly attachments and the rigors of urban life. This first poem of his northern journey expresses a tender, solemn awareness: that the road ahead lies in the flow of time and nature’s cycles. By opening his travelogue with this verse, Basho set the emotional tone for the long pilgrimage—rooted in transience, humility, and sensitivity to the seasons.

Basho’s Vision

Basho’s vision in this haiku is to reveal the profound unity between human feelings and the natural world. The farewell to spring is not a private sentiment but something mirrored in the birds’ cries and the glistening eyes of the fish.

As he set off from Senju, Basho saw the journey itself as part of the great rhythm of life—birth, passing seasons, departure, and return. His poetry invites us to perceive that nature’s changes echo each transition in our lives, and to embrace travel not merely as movement in space but as a spiritual passage in time.

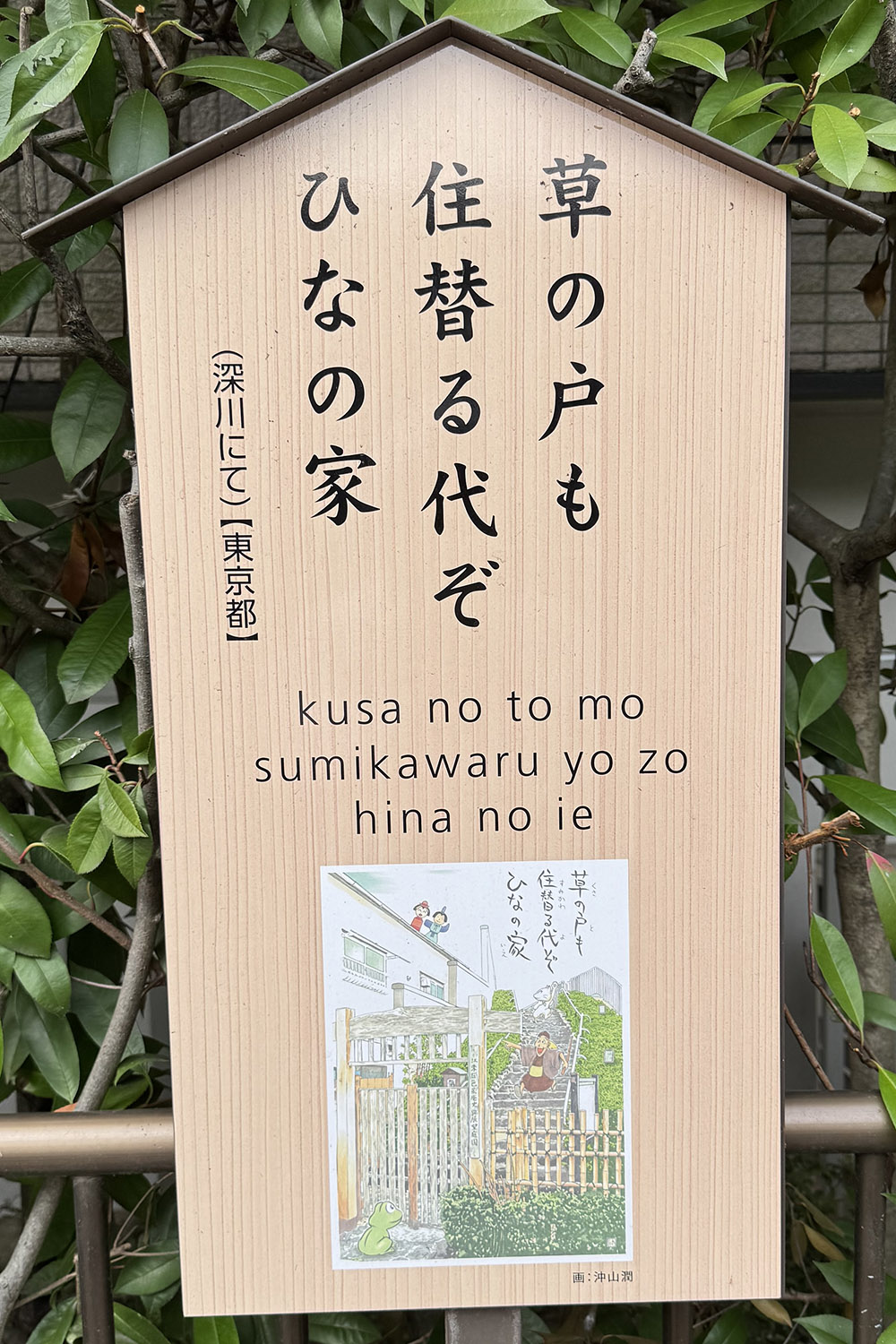

Haiku 17. Location: Fukagawa, Tokyo

草の戸も 住替る代ぞ ひなの家

(Kusa no to mo / Sumikawaru yo zo / Hina no ie)

Even this grass-thatched hut—

in the changing age

becomes a doll-display house.

Behind the Haiku - Discover the hidden stories behind each haiku –

1. The setting: Basho’s humble hut in FukagawaThis poem was composed in Fukagawa, on the eastern bank of the Sumida River in Edo (present-day Tokyo), where Basho spent several years in a rustic hut known as the Basho-an. The hut was simple, with a thatched roof—hence the phrase “kusa no to” (grass-thatched door or hut), often used in classical poetry to evoke a humble, almost hermit-like dwelling.

Basho wrote this haiku when he was about to move out of the hut before setting off on his remarkable journey recorded in Oku no Hosomichi (The Narrow Road to the Deep North). The verse captures the moment of leaving behind a place that had been both a home and a retreat for poetic contemplation.

2. The seasonal and cultural reference: Hina dolls and new beginnings

The phrase “Hina no ie” refers to a house displaying dolls for the Girls’ Festival (Hina-matsuri), celebrated on the third day of the third lunar month (early spring). In Edo-period Japan, this festival marked both the welcoming of spring and prayers for the healthy growth and happiness of girls.

The haiku suggests that the humble hut, once Basho’s quiet retreat, will soon be occupied by a new resident who will celebrate the festival with bright dolls. The image evokes a striking contrast: the transience of a poet’s simple abode giving way to the cheerful, decorative world of a young girl’s festival.

3. A reflection on impermanence and change

The phrase “Sumikawaru yo zo” literally means “times change and people move.” Basho acknowledges the inevitable cycles of change—homes pass from one occupant to another, lives transform, seasons turn.

By noticing this transformation of his hut from a rustic poet’s dwelling into a festive household, Basho captures the bittersweet truth of impermanence (mujō), yet with a gentle humor and warmth. It is not a lament but an acceptance of the natural flow of time.

Basho’s Vision

Basho’s vision here is to reveal that the essence of life lies in the quiet transitions—from one season, one dwelling, one chapter of life to another. His haiku invites us to see beauty not only in the unchanging but in the very fact of change itself.

The image of the grass hut giving way to a house adorned with dolls reflects the coexistence of simplicity and festivity, austerity and joy. For Basho, each change—however humble—holds poetic meaning and reminds us that every dwelling, like every human life, is but a temporary stop along the greater journey.

Closing Message:

With this installment, our six-part Basho Haiku Walkway comes to an end. We have journeyed together from the heart of Edo to the fields of the north, tracing the footsteps of Basho and glimpsing the world as he saw it—alive with the seasons, full of departures and returns.We sincerely thank you for accompanying us on this poetic journey. We look forward to welcoming you again in our future projects, where we will explore new selections of haiku—revealing fresh perspectives on nature, travel, and the human spirit.